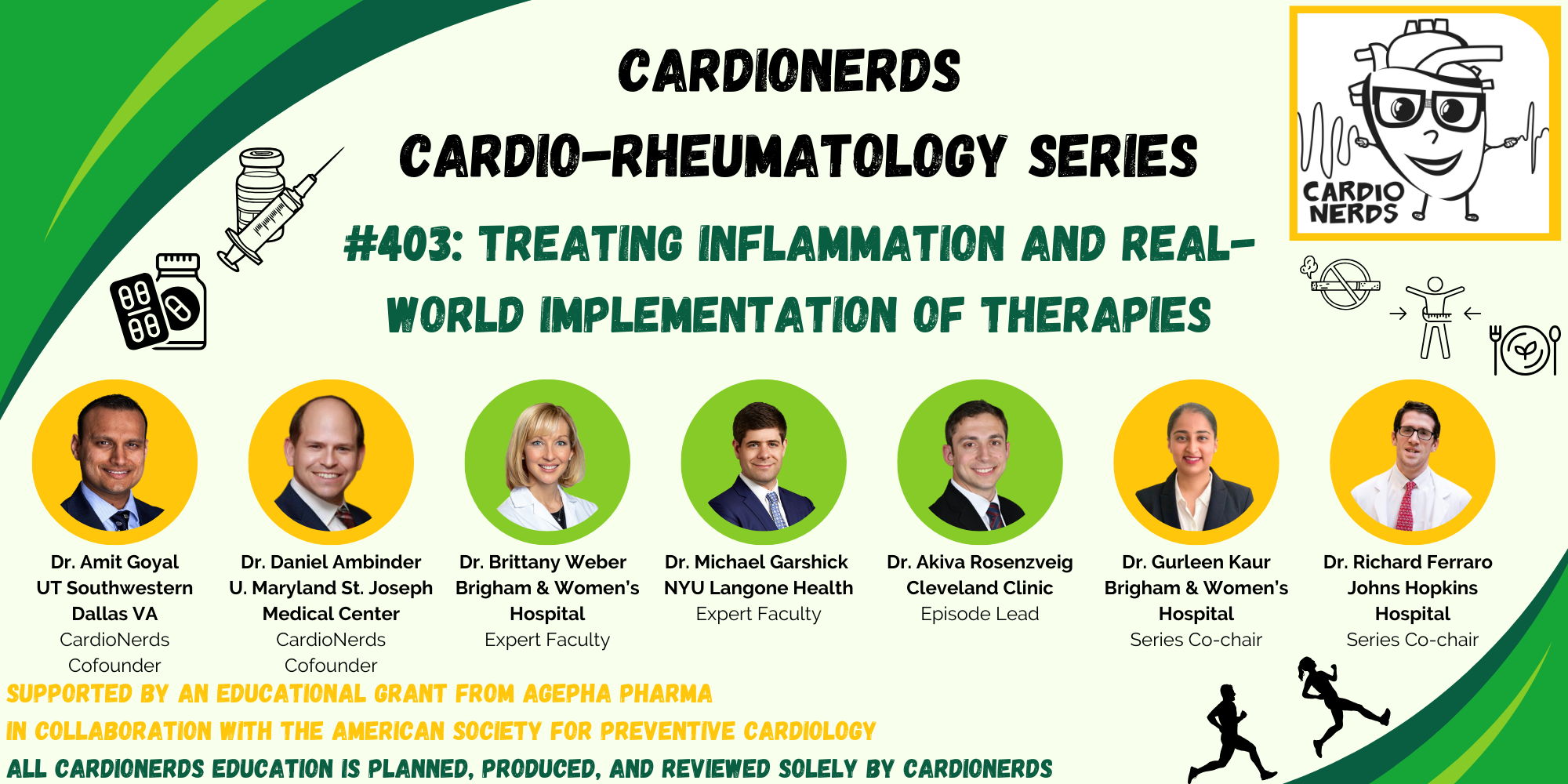

In this episode, CardioNerds Dr. Gurleen Kaur and Dr. Akiva Rosenzveig are joined by Cardio-Rheumatology experts, Dr. Brittany Weber and Dr. Michael Garshick to discuss treating inflammation, delving into the pathophysiology behind the inflammatory hypothesis of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease and the evolving data on anti-inflammatory therapies for reducing ASCVD risk, with insights on real-world implementation.

Show notes were drafted by. Dr. Akiva Rosenzveig.

This episode was produced in collaboration with the American Society of Preventive Cardiology (ASPC) with independent medical education grant support from Agepha Pharma.

US Cardiology Review is now the official journal of CardioNerds! Submit your manuscript here.

Pearls – Treating Inflammation

Our understanding of the pathophysiology of atherosclerosis has undergone a few iterations from the incrustation hypothesis to the lipid hypothesis to the response-to-injury hypothesis and culminating with our current understanding of the inflammation hypothesis. Both the adaptive and innate immune systems play instrumental roles in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. After adequately controlling classic modifiable risk factors such as blood pressure, dyslipidemia, glucose intolerance, and obesity, systemic inflammation as assessed by CRP can be ascertained as CRP is associated with ~1.8-fold increased risk of cardiovascular events Although the most common side effect of colchicine is gastrointestinal intolerance, colchicine can induce lactose intolerance, so a lactose free diet may help ameliorate colchicine-induced GI symptoms. Anti-inflammatory therapeutics have shown promise in reducing cardiovascular risk but much more is to be learned with ongoing and future basic, translational, and clinical research.Show notes – Treating Inflammation

What are the origins of the inflammatory hypothesis?The first hypothesis as to the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis was the incrustation hypothesis by Carl Von Rokitansky in 1852. He suggested that atherosclerosis begins in the intima with thrombus deposition.In 1856, Rudolf Virchow suggested the lipid hypothesis whereby high levels of cholesterol in the blood lead to atherosclerosis. He observed inflammatory changes in the arterial walls associated with atherosclerotic plaque growth, called endo-arteritis chronica deformans.In 1977, Russell Ross suggested the response-to-injury hypothesis, that atherosclerosis develops from injury to the arterial wall.In the 1990’s the role of inflammation in ASCVD became more recognized. Both the adaptive and innate immune system are critical in atherosclerosis. Lipids and inflammation are synergistic in that lipid exposure is required but they translocate through damaged endothelium which occurs by way of inflammatory cytokines, namely within the NLRP3 inflammasome (IL-1, IL-6 etc.).Smooth muscle cells are also involved. They migrate to the endothelial region and secrete collagen to create the fibrous cap. They can also transform into macrophage-like cells to take up lipids and become foam cells. T, B, and K cells are also part of this milieu. In fact, neutrophils, macrophages and monocytes make up only a small portion of the cells involved in the atherosclerotic process. What are ways to individually optimize one’s ASCVD risk?Ensure the patient is on appropriate antiplatelet therapy, lipid lowering therapy, blood pressure is well controlled, and the Hemoglobin A1c is well controlled. Smoking cessation is pivotal. If the patient has an elevated Lipoprotein (a), pursue more aggressive lipid lowering therapy. Targeted therapies may become available in the future. Assess the patient’s systemic inflammatory risk as measured by C-Reactive Protein (CRP) What is the evidence for utilizing CRP in risk stratification?CRP, initially termed Fraction C (discovered as a c polysaccharide component of the pneumococcal cell wall), was first discovered at Rockefeller University in the 1930’s. It was discovered to be an acute phase reactant in the 1940’s and noted to be synthesized in the liver in the 1960’s. Although it is not causal in atherosclerosis, elevated CRP is associated with elevated rates of cardiovascular disease. This was first noted in the landmark New England Journal of Medicine study by Ridker et al that showed elevated CRP was associated with elevated cardiovascular risk and treating with anti-inflammatory medication (aspirin) lowered CRP and CV risk. The statin trials also showed reduction in CRP levels was associated with better outcomes. High-sensitivity CRP (hsCRP) >3 mg/L has odds ratio of ~1.8 for risk of CV disease. Recent analyses of the PROMINENT, REDUCE-IT, and STRENGTH trials demonstrated that hsCRP was a more powerful determinant of recurrent CV events, CV death, and all-cause mortality than LDL-C. After effectively controlling the previously stated modifiable risk factors, what therapeutic options remain in a patient with an elevated CRP?CANTOS trial was the first proof of concept trial investigating Canakinumab (an IL-1 inhibitor) which showed a ~15% relative risk reduction in cardiovascular events CIRT trial investigated methotrexate in patients without autoimmune disease. It was stopped early due to it being a negative trial. This emphasized the complex role inflammation plays in ASCVD, and that both patient selection and chosen anti-inflammatory therapy are important to consider for ASCVD risk reduction. Colchicine has seen a lot of focus in this space with trials such as COLCOT, COPS, LODOCO, LODOCO 2, LODOCO MI. Overall, it appears that colchicine may be more effective in chronic stable ischemic heart disease. The CLEAR SYNERGY trial investigated colchicine in the peri-MI period and was a negative trial. However, we do not yet have the published data to further analyze it. A review article by Potere et al (referenced below) provides a useful summary of novel therapies and upcoming trials in the inflammation in ASCVD space. How do we approach inflammation in women?We know that immune response differs between men and women. Women have more robust immune response to vaccines and viruses and greater innate and adaptive immune responses. Women have slightly higher CRP than men. Studies have shown that average high sensitivity hsCRP is 1.7 for women and 1.2 for men. In the JUPITER trial, the subgroup of patients with hsCRP>7 mg/L had the highest proportion of women relative to men. Regardless, hsCRP remains a reliable predictor of CV events in both men and women. What are some practical considerations when starting colchicine?It may help with adherence, if you walk patients through what to expect with the medication. Obtain renal and liver function tests as both organs contribute to colchicine metabolism and clearance. Obtain a thorough medication reconciliation as colchicine has some notable drug-drug interactions. The most common side effects is GI intolerance; cytopenias are rare occurrences. Note that colchicine can induce lactose intolerance, a potential mechanism for causing GI intolerance, so a lactose free diet may help with adherence. What do we have to look forward to in the anti-inflammation space in CV disease?There is still a lot to be learned and discovered in this space. Some clinical trials to look out for are the ZEUS, ARTEMIS, and HERMES trials which look at Ziltivekimab, an IL-6 inhibitor, in chronic kidney disease, acute myocardial infarction, and heart failure, respectively.References – Treating Inflammation